Following the rapid contraction in U.S. economic activity as a result of the outbreak of COVID-19, the unemployment rate spiked to 14.4 percent in April and remained elevated in May (13.0 percent), setting the mark for the two highest recorded rates in the post-World War II era. Despite the federal foreclosure moratorium, there were fears that up to 30 percent of homeowners would require forbearance, ultimately leading to a foreclosure tsunami. Forbearance did not hit 30 percent, but rather peaked at 8.6 percent and has been steadily falling since. Even so, forbearance does not equal foreclosure, and focusing on mortgage delinquency rates alone ignores the dual trigger responsible for foreclosure – economic hardship and lack of equity. The rising inability to pay in this crisis is unlikely to lead to large amounts of foreclosure activity because homeowners have more equity than ever before.

“Alone, economic hardship and a lack of equity are each necessary, but not sufficient to trigger a foreclosure. It is only when both conditions exist that a foreclosure becomes a likely outcome.”

The Dual Trigger

Foreclosure is a two-step process. First, the homeowner suffers an adverse economic shock, such as a loss of income, serious illness, or the death of a spouse, leading to the homeowner becoming delinquent on their mortgage. However, not every delinquency turns into a foreclosure. With enough equity, a homeowner has the option of selling the home or those with stable incomes can tap into their equity through a refinance to help weather the economic shock. The reverse is also true: if the homeowner has little equity in their home but suffers no financial setback that leads to delinquency, there’s no need for a foreclosure. This is what we call the “dual trigger hypothesis.” Alone, economic hardship and a lack of equity are each necessary, but not sufficient to trigger a foreclosure. It is only when both conditions exist that a foreclosure becomes a likely outcome.

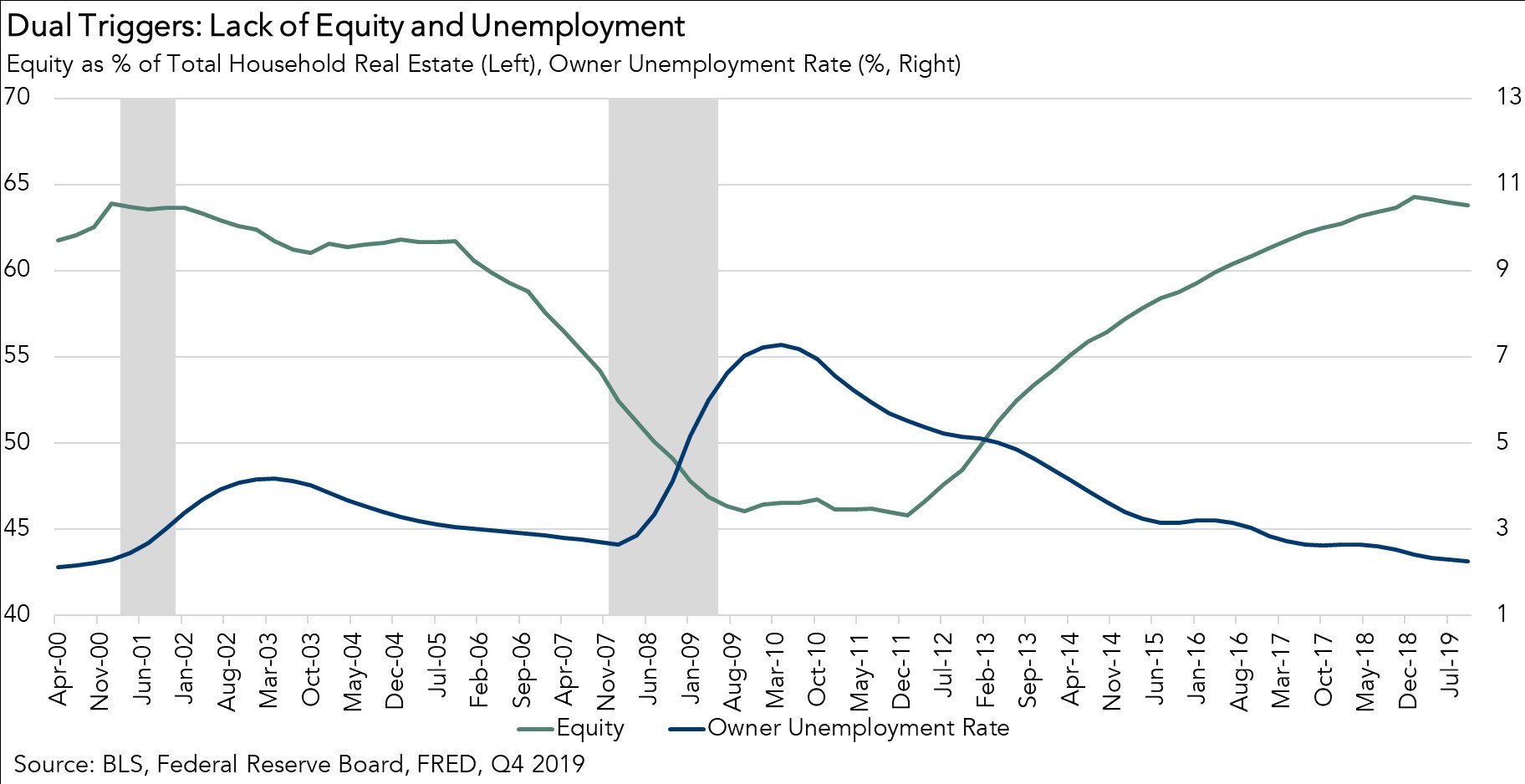

Consider how different foreclosure trends were in the two previous recessions. The 2001 recession led to a rise in unemployment without a comparable rise in foreclosure activity. The unemployment rate among homeowners increased from 2.5 percent in the second quarter of 2001 to 3.7 percent in the same quarter the following year, a 1.2 percentage point increase. Yet, the average number of new foreclosures barely increased. This was largely because of high household equity, which nationally was nearly 64 percent in the quarter leading up to the 2001 recession, 12 percent above the historical average.

During the Great Recession, high levels of housing debt combined with declining house prices resulted in a 5.6 percentage point decline in household equity, from 52.5 percent to 46.9 percent, between the first quarter of 2008 and second quarter of 2009. Paired with soaring unemployment, which more than doubled for homeowners over the same time period, the dual trigger produced a wave of foreclosures, as foreclosure starts quadrupled compared with their pre-recession pace.

This Time, It’s Different

There are two main reasons why this crisis is unlikely to produce a wave of foreclosures similar to the 2008 recession. First, the housing market is in a much stronger position compared with a decade ago. Accompanied by more rigorous lending standards, the household debt-to-income ratio is at a four-decade low and household equity near a three-decade high. Indeed, thus far, MBA data indicates that the majority of homeowners who took advantage of forbearance programs are either staying current on their mortgage or paying off the loan through a home sale or a refinance.

Second, this service sector-driven recession is disproportionately impacting renters. Our research finds that historically the average unemployment rate gap between renters and owners is 4.4 percentage points. Recessions have typically widened that gap, largely because homeownership is correlated with being older and more educated. Unlike a typical recession, this crisis hit hardest in the service sector, which employs mostly younger, less educated workers. According to data from the Census Pulse Survey, averaging across the four weeks of June, 53 percent of renter households experienced a loss of employment income, compared with 39 percent of owner households.

Housing on a Path Towards Recovery

With a resurgence of COVID-19 cases and local shutdowns, mortgage delinquencies are on the rise. However, homeowners today have much more equity in their homes than in the lead up to the Great Recession, largely negating the second of the two triggers necessary for a foreclosure. New foreclosures during the Great Recession peaked in the third quarter of 2010 at 274,000, with a homeowner unemployment rate of 7.2 percent. If unemployment reached that level today, we would expect less than 167,000 (nearly 40 percent fewer) new foreclosures in the second quarter of 2020 due to the higher levels of equity homeowners have today. Some foreclosures are still likely to happen, and trends will vary by geography, but this time it’s different – only one of the dual triggers exists today.

Ksenia Potapov contributed to this blog post.