The importance of measuring housing affordability is paramount. Homeownership is synonymous with the American Dream and all of the wealth-building benefits that it provides, and housing is the single largest monthly expense for most households. Yet, there are many ways to measure the affordability of housing.

One traditional method that has received more attention recently is the ratio between house prices and median household incomes, or the price-to-income ratio. This is a particularly nice and simplified way of measuring affordability because the link between income, which consumers use to pay the mortgage, and house prices is intuitive. The higher the income, the more house one can afford. If house prices are growing at a faster rate than incomes, the ratio will rise and affordability will decline. If, on the other hand, income growth outpaces house price growth, the ratio will move lower and affordability will increase.

“Slow income growth isn’t causing an affordability crisis. Low mortgage rates are causing an affordability boon.”

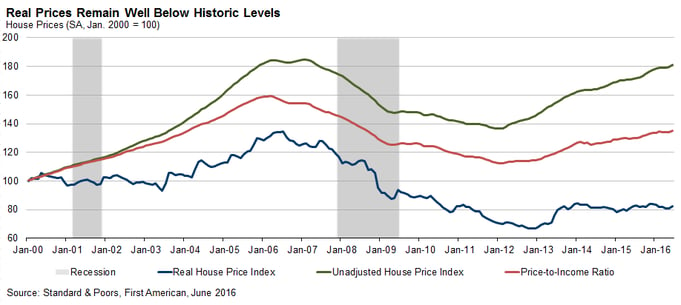

In Figure 1, we compare the unadjusted Case-Shiller house price index with the price-to-income ratio created using the same index and median household incomes from BLS. They are both indexed so that January 2000 is equal to 100. It is easy to see that unadjusted house prices grew much faster than incomes in the early to mid-2000s. In fact, by the time of the housing boom peak in March 2006 house prices had grown 59.4 percent more than incomes. The historical decline in house prices that occurred during and following the Great Recession helped to bring house prices more in line with median income. By January 2012, the price-to-income ratio was only 12.4 percent higher than it was at the very beginning of the aughts.

FIGURE 1:

However, the house price gains observed since the trough in 2012 have been substantial in many markets. As the price-to-income ratio shows, house prices have exceeded the growth of median household income since 2012. Hence the fear and hand wringing about affordability because house price growth exceeding income growth is a clear indication of falling affordability for the first-time homebuyer, right? We are in the midst of an affordability crisis, which is why we don’t have more first-time homebuyers in the market, right?

Not right!

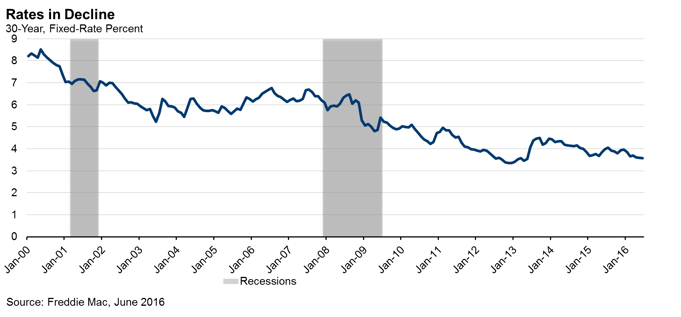

Of course, many potential homebuyers, especially those who are rent burdened, do face significant affordability and access to credit challenges, but a rising price-to-income ratio is not a sufficient condition to indicate an affordability crisis. This is because the price-to-income ratio does not account for an important factor -- the impact of the mortgage rate on the consumer’s ability to leverage their income when purchasing a home. The average 30-year, fixed mortgage rate in July 2016 was 3.43 percent according to Freddie Mac’s Primary Mortgage Market Survey. This is the lowest it’s been since Freddie Mac started tracking interest rates in 1971, excluding a four-month period between October 2012 and January 2013 when rates moved between 3.35 and 3.41 percent (see Figure 2). With rates at such low levels, borrowers are able to afford more housing than if the rates were at 6.29 percent, which is the average rate borrowers received between 2000 and 2009. Even with slow or no real household income growth, falling mortgage rates increase consumer house-buying power.

FIGURE 2:

By taking the house-buying power influence of interest rates into account, the First American Real House Price Index (RHPI), takes the price-to-income concept one step further and adjusts house price growth to reflect growth in median household income and the change in house-buying power caused by mortgage rate changes. Looking again at Figure 1, the RHPI shows that after taking mortgage rates into account, in May 2016 house prices were still 39.6 percent below the peak reached in July 2006 and 19 percent below where they were in January 2000. Further, in terms of real homebuyer purchasing power, the march of interest rates downwards since September 2013 has in a large part mitigated the growth in house prices over the same period. So, while lackluster growth in median household income is a real concern for many reasons, its inability to keep pace with house price growth is overhyped relative to the real affordability benefit that the low interest rate environment has been for consumers. Today’s era of low interest rates have increased consumer purchasing power, allowing them to leverage their income into more housing and keeping housing affordability in check.

By taking the house-buying power influence of interest rates into account, the First American Real House Price Index (RHPI), takes the price-to-income concept one step further and adjusts house price growth to reflect growth in median household income and the change in house-buying power caused by mortgage rate changes. Looking again at Figure 1, the RHPI shows that after taking mortgage rates into account, in May 2016 house prices were still 39.6 percent below the peak reached in July 2006 and 19 percent below where they were in January 2000. Further, in terms of real homebuyer purchasing power, the march of interest rates downwards since September 2013 has in a large part mitigated the growth in house prices over the same period. So, while lackluster growth in median household income is a real concern for many reasons, its inability to keep pace with house price growth is overhyped relative to the real affordability benefit that the low interest rate environment has been for consumers. Today’s era of low interest rates have increased consumer purchasing power, allowing them to leverage their income into more housing and keeping housing affordability in check.

This is a much different picture than the one painted by looking at a simple house price index or a price-to-income ratio. As long as this low-rate environment persists, which seems highly likely for the foreseeable future due to the paradoxical influence of global economic uncertainty on U.S. mortgage rates, potential homebuyers will continue to benefit. Today’s increased purchasing power and affordability remain at greater levels than those experienced in the early 2000’s prior to the run-up in prices due to the housing boom. Slow income growth isn’t causing an affordability crisis. Low mortgage rates are causing an affordability boon.