September is commonly associated with the beginning of the school year, but it also signals the end of the peak home buying season. The tapering of the housing market in September is part of its normal annual cycle, which follows the same general pattern of peaks and troughs every year, with one big exception. In 2020, the pandemic was the catalyst for an unusually strong fall housing market. As we turn to fall once again, the question remains, will the housing market’s traditional seasonality return once pandemic-related disruptions wane, or is there reason to believe that housing market seasonality is weakening for reasons not directly tied to the pandemic?

“It is possible that seasonality will be less pronounced than in the past, even after the acute disruptions caused by COVID-19 moderate.”

What Drives Housing Market Seasonality?

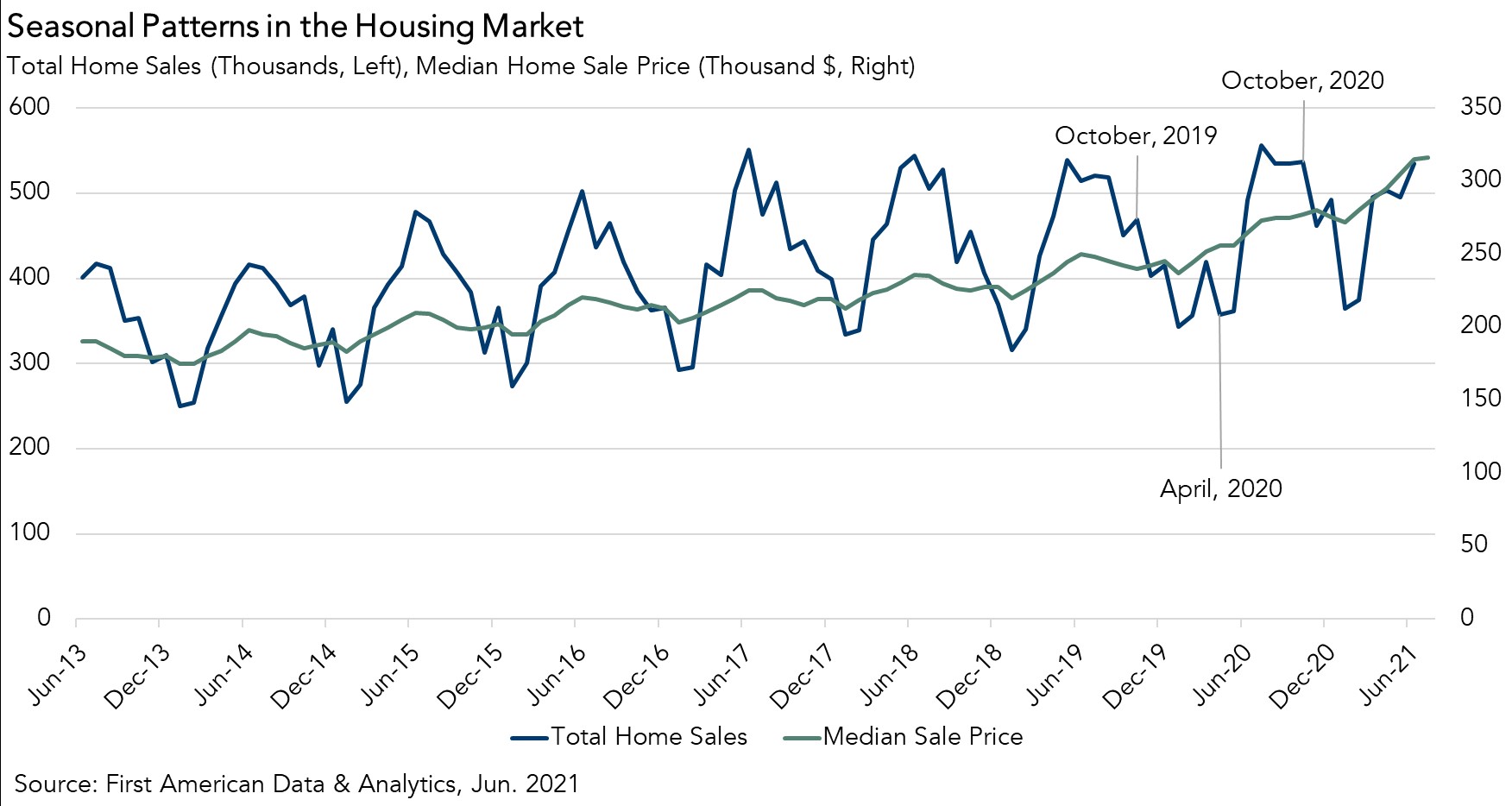

Home-buying activity tends to follow predictable seasonal patterns. Home buyers overwhelmingly move in the spring and early summer months, making it the busiest time to buy and sell. Between 2013 and 2019, home sales were on average 75 percent higher during the peak (which usually occurs in June) compared with the trough of the previous winter (which usually occurs in January). During the same period, median home sale prices followed a similar seasonal pattern and were 13 percent higher on average during the annual seasonal peak compared with the trough.

Housing market seasonality also shows up in housing market velocity data as measured by median days on market, and in housing supply data as measured by the number of active listings of homes for sale. In short, supply and demand increase in the spring and summer months. In the fall and winter, the market cools down as home sales slow and the median home sale price declines relative to the summer peak, resulting in fewer homes available for sale and those that are available tend to stay on the market for longer.

The housing market’s seasonal pattern was driven by weather, holidays and the traditional school year schedule. Families with school-aged children tend to move in the summer to avoid disrupting their children’s school year. People also tend to move in the spring and summer because of warmer temperatures and a lower chance of inclement weather. The barrage of holidays and the colder weather during the winter make it a less ideal time to move.

This seasonal pattern can become self-reinforcing. A person without any children may still decide to move in the summer because housing supply increases and there are more homes to choose from. An existing homeowner might sell their home during the peak months hoping for a higher sale price. Of course, the typical seasonal pattern played out differently in 2020.

COVID-19 Disrupts the Norm

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic disrupted the housing market’s traditional seasonal pattern. First, the housing market froze in the early spring of 2020 as mandated lockdowns and social distancing measures made it difficult to buy and sell homes. Then, in June 2020, the housing market rebounded. Historically low mortgage rates increased house-buying power, consumer preferences shifted towards more space, and people that kept their jobs and worked from home saw their savings increase – savings which could be used toward a down payment.

The pause in April and May extended the summer home-buying season into the fall and winter of 2020. Both home sales and home price growth were uncharacteristically strong. Home sales in the fourth quarter of 2020 were 16 percent higher than a year before and prices were 15 percent higher. Was this just a one-time event caused by an unleashing of pandemic pent-up demand or are there other dynamics at play that may signal a change to the housing market’s seasonal pattern?

Potential Reasons for Weaker Seasonality

Housing market seasonality may be less defined in the future, even once the acute effects of the pandemic recede. One reason is that investor activity doesn’t typically follow the same seasonal trends as the rest of the market. For investors and second-home buyers, movements in mortgage rates are more consequential. Markets with a higher or growing share of investor activity should expect less seasonality.

Another potential reason for less seasonality are the demographic trends that, combined with the continued housing supply shortage, may stretch buying activity past the traditional home-buying season. Millennials make up the largest share of first-time home buyers today, and that is expected to remain so as the generation ages into its prime home-buying years. The lack of inventory and resulting intense bidding wars throughout the spring of 2021 left many potential millennial home buyers unable to find something to purchase, and many of them may find a home to buy in the fall or winter rather than walk away from the market until the following spring. It helps, of course, that millennial households are less likely than previous generations to be concerned with school schedules. According to 2019 ACS data, only 51 percent of households headed by 24-39-year-olds had children, compared with 60 percent of similar households in 2000.

The pandemic led to numerous disruptions in the housing market, resulting in unseasonably strong home-buying activity in the fall and winter months of 2020. However, it is possible that seasonality will be less pronounced than in the past, even after the acute disruptions caused by COVID-19 moderate.

Ksenia Potapov contributed to this blog post.