Many people understand the “natural rate of unemployment,” and if you don’t, you can probably guess what it is – the rate of unemployment when the labor market reaches equilibrium. What many people don’t know is that a similar concept exists in monetary policy.

“Understanding why we have a historically low neutral rate of interest provides insight into the Fed’s decision-making process as it calibrates the federal funds rate – a key tool in the central bank’s toolkit.”

The U.S. Central Bank uses its ability to adjust the short-term federal funds rate as its primary policy tool to influence the economy. When determining where to set the federal funds rate, the U.S. Central Bank considers what the natural, also known as the “neutral,” rate of interest is.

The neutral rate of interest is unobservable, but it can be estimated based on analysis of a variety of economic indicators. In its most basic form, it is the short-term interest rate that would prevail when the economy is at full employment and stable inflation. In other words, an equilibrium rate of interest that is neither expansionary nor contractionary. The neutral rate of interest can inform monetary policy decisions, signaling whether the Central Bank’s interest rate policy is stimulating or contracting the economy.

Several Factors Driving Down the Price of Capital

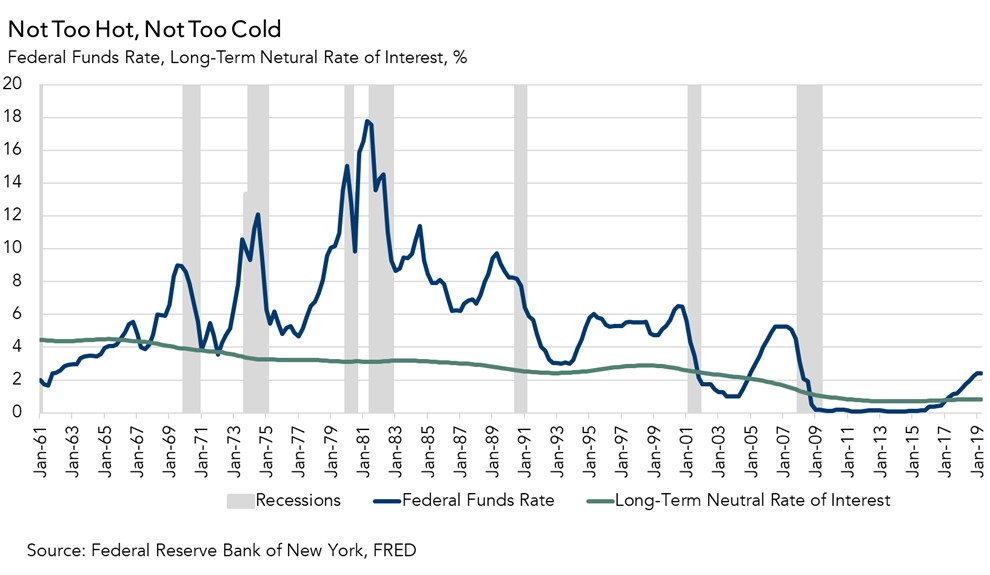

In the long run, the neutral rate of interest is determined by the supply and demand for savings (income that is not used for immediate consumption and is the capital that can be invested back into the economy). The chart below compares the neutral rate of interest, the real interest rate expected to prevail when the economy is at full strength and inflation is stable, with the actual federal funds rate.

Current estimates show that the federal funds rate has been higher than the neutral rate of interest since the fourth quarter of 2017. U.S. monetary policy as expressed by the federal funds rate is at a level similar to the early 1960’s, which may seem to many to be geared toward promoting economic expansion. However, when you compare today’s federal funds rate with the neutral rate of interest, it implies that U.S. monetary policy may actually be contractionary right now. How can a federal funds rate at the same level be expansionary in the 1960s, but contractionary now? The neutral rate of interest is significantly lower today. So, why is the neutral rate of interest at a 60-year low?

The neutral rate of interest is at a historically low level today because there is an excess of global savings relative to the demand for that money for investments. Therefore, the neutral rate of interest represents the equilibrium point, or price, for savings which is determined by the supply of savings and the demand for investment. Several factors impact this supply and demand dynamic.

1. Productivity and Demographics

The current economic expansion may be the longest in the nation’s history, but it has also been one of the slowest expansions in terms of cumulative growth since the start of the expansion. The economy has expanded at an average of just 2.3 percent a year since the recession ended in June 2009, which is well below the 3.6 percent annual growth rate during the 1990s expansion and the 4.2 percent growth rate in the 1980s expansion.

This is partly because the workforce is growing more slowly. Retirements have accelerated during the recovery, while young people have stayed in school longer, making them less likely to work. The workforce has grown just 0.5 percent a year, on average, for the past decade — barely one-third the pace of its growth in the 1980s and 1990s expansions.

Slower productivity growth also plays a role. Low productivity growth means businesses are less likely to seek capital for investment opportunities. This decreases the demand for capital, so the price of capital – interest rates – declines.

2. Secular Stagnation

Economist Alvin Hansen coined the term secular stagnation in the 1930s, following the Great Depression. He used it to describe a chronic lack of investment demand relative to capital supply. In this context, “secular” referred to the long-term nature of the stagnation. Today, secular stagnation refers to a long period of high global capital savings relative to low demand for capital investment. An economy characterized by high capital savings, but low investment demand, means the price of capital – the neutral rate of interest – goes down.

3. Flight to safety

Our domestic economy is more globally interconnected than ever before, supported by a complex network of supply chains for the production of goods and financial markets that are connected in near real-time. One outcome of this globally connected financial market is that when uncertainty increases globally, the demand for safe harbor assets, like U.S. treasuries, increases. Put another way, global uncertainty creates a flight to the safety and security of U.S. government long-term Treasury bonds, which increases the supply of capital domestically and drives down the neutral rate of interest.

The neutral rate of interest is lower than the federal funds rate in the United States, as well as in other major economies such as Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom. This is not just a domestic phenomenon. For the Federal Reserve and other central banks, low neutral rates of interest limit their ability to respond to recessions. If the neutral rate of interest in the U.S. were to fall further, the Federal Reserve may need to apply tools other than the federal funds rate for expansionary monetary policy in the event of a recession. Until then, understanding why we have a historically low neutral rate of interest provides insight into the Fed’s decision-making process as it calibrates the federal funds rate – a key tool in the central bank’s toolkit.