The dual mandate of the Federal Reserve is to maintain stable inflation and full employment, and while the latter goal has mostly been achieved post-pandemic, the former remains far from target. One of the primary instruments of monetary policy the Fed uses to achieve its dual mandate is controlling the federal funds rate. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) recently announced a 50-basis point hike in that all important rate, with more rate hikes to come. The message from the Fed is clear - it’s imperative to get inflation under control and it will act aggressively to do so. But just how aggressive will the Fed need to be?

Keep the Economy in Neutral

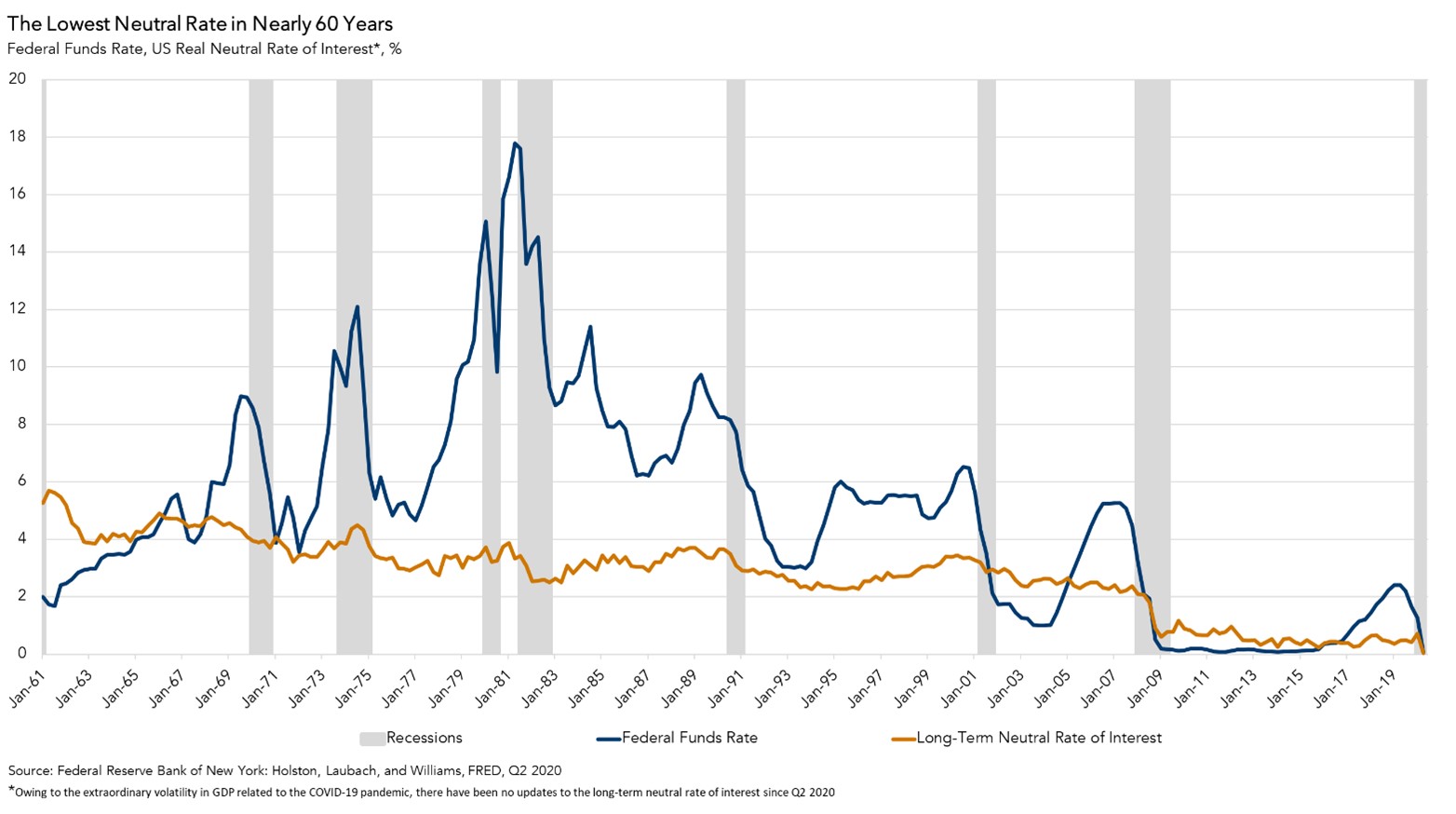

When determining where to set the federal funds rate, the Fed studies a multitude of models and analyses, including the neutral rate of interest, also known as r-star. The neutral rate of interest is the short-term interest rate level when the economy is at full employment and inflation is stable, and it is discussed in real terms (with inflation subtracted out). Think of r-star as the ideal but elusive “price” for money. The lower the r-star, the cheaper the price of money necessary to achieve that full-employment and inflation balance, and vice-versa. The Fed may choose to set the benchmark federal funds rate above the neutral rate to cool the economy, because that makes the price of money relatively expensive, or it could make the price of money relatively cheap by setting the federal funds rate below the neutral rate to stimulate the economy.

While the neutral rate cannot be observed directly, it can be estimated. Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, has suggested that the Fed believes that the neutral rate is currently somewhere between 2 and 3 percent, assuming an inflation rate of 2 percent. Powell has insisted that the Fed “will not hesitate” to go beyond the neutral rate if warranted by the economic data this summer, which means the federal funds rate may need to go even higher than 2 to 3 percent to cool inflation.

Prior to the pandemic, the neutral rate was at a 60-year low of 0.7 percent and below the federal funds rate, according to estimates from Holston, Laubach and Williams. In fact, the neutral rate of interest just before the pandemic was significantly lower than it was prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and had remained at this low level in the years after the GFC and all the way through the pandemic.

The very low neutral rate phenomenon is not contained to the U.S., it is similar for other advanced economies. One of the explanations is that the price of money – the neutral rate of interest – is low because the economy is in a new era of secular stagnation. Secular stagnation in this context refers to a long period of high global capital savings relative to low demand for capital investment. Some of the key drivers of this secular stagnation are: global graying of the population, which has resulted in excess savings; slower productivity growth, which has reduced demand for capital investment; and the U.S. serving as a safe haven for foreign assets, which has exacerbated the savings glut domestically, putting downward pressure on the neutral rate of interest.

Yet, new research suggests that the decline in the neutral rate of interest reflects not demographic and savings factors, but rather a “hall of mirrors” effect in which lower rates change private-sector behavior in ways that lower the neutral rate. The Fed and the private sector are each reacting to the other’s moves and interpreting each other’s expectation of the elusive, unobservable neutral rate. This would have very different policy implications than the reasons previously cited. The demographic and savings explanations for a low neutral rate cannot be changed easily by policymakers, but a hall-of-mirrors explanation may allow for change by signaling a clear expectation to the private sector.

The Elusive Neutral Rate

Pinning down the neutral rate of interest is difficult on a normal year, but it’s even more of a moving target in such an uncertain year. Whether the neutral rate is between 2 to 3 percent or has drifted higher, the message from Chairman Powell is clear -- the Fed remains data dependent and will raise the federal funds rate as far as needed to reach stable inflation. If supply chain bottlenecks ease and inflation meets the Fed in the middle, it’s possible that the Fed may not need to be as aggressive in raising rates. But, if inflation remains stubbornly high, the Fed may need to shift gears from neutral to drive by pushing rates above neutral to shoot for the “r-star.”