Given both emergency rate cuts of the Federal Reserve and the recent economic uncertainty due to the spread of the Coronavirus, the 10-year Treasury yield dropped to its lowest level in 150 years, according to Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller. For added perspective, that takes us back to the time of Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency. The 10-year Treasury bond is often known as the “risk-free” benchmark for financial transactions worldwide. Due to recent economic uncertainty stemming from the evolving coronavirus situation, investors fled stocks and rushed to bonds, pushing yields down.

“So, how low can mortgage rates go? Today’s rates are already really close to the bottom.”

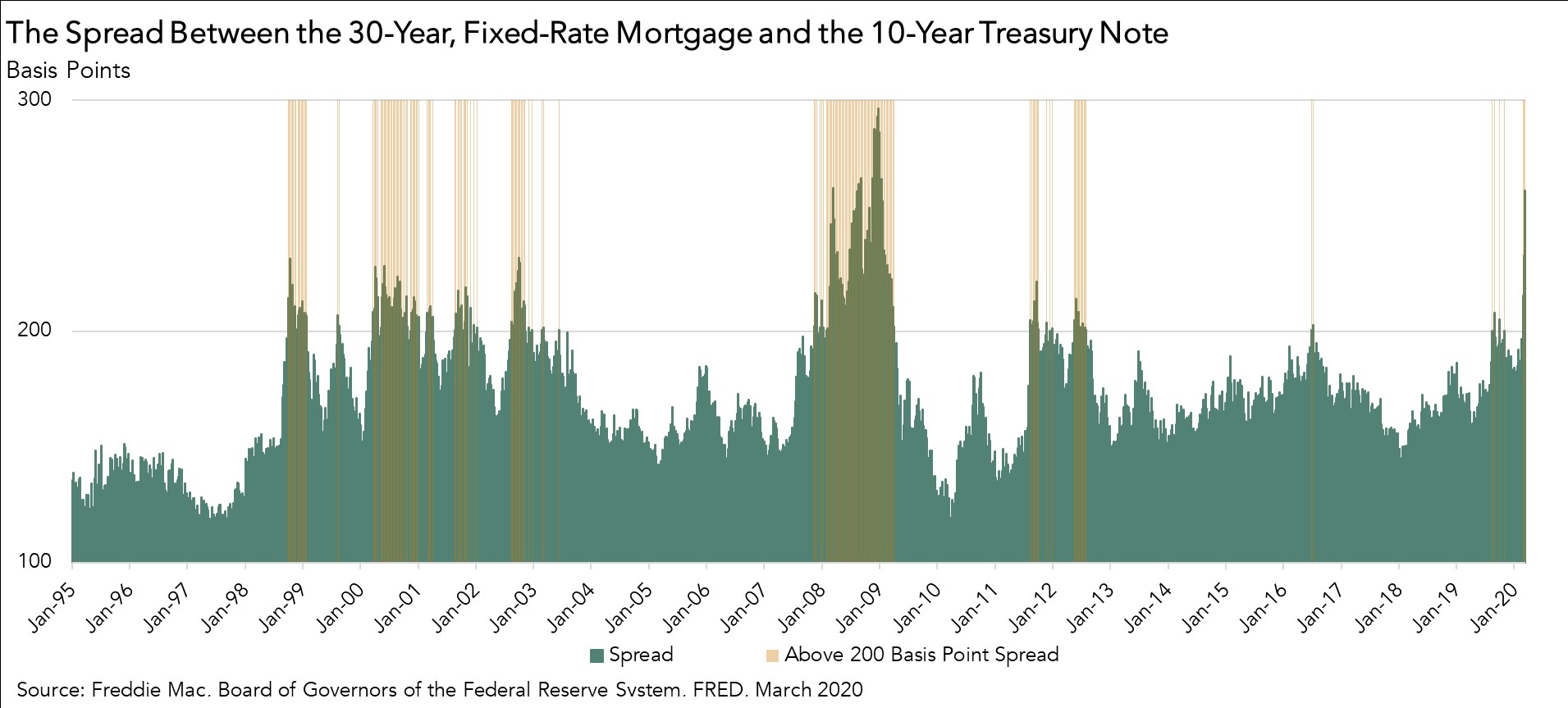

With yields taking a nosedive, real estate professionals and housing market observers expect lower rates on the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. Why? The popular 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage is loosely benchmarked to the 10-year Treasury bond. In fact, since the end of the Great Recession, the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage has on average remained 1.7 percentage points (170 basis points) higher than the 10-year Treasury bond yield. With plunging yields and several nations such as Japan and Sweden already experiencing negative interest rates, it begs the question – will mortgage rates fall by the same magnitude as the 10-year Treasury, and what does a potential negative interest rate scenario mean for mortgage rates?

Will Mortgage Consumers Reap the Full Windfall of Declining Yields?

While the average spread between the 10-year Treasury and mortgage rates has been approximately 170 basis points in the post-recession period, this does not mean that this spread is always consistent. In fact, given the most recent 10-year Treasury of 0.7 percent, the historical spread implies a mortgage rate of 2.4 percent, yet economists believe the mortgage rate will not move below 3 percent in the near term.

There is historical precedent that shows the spread tends to widen to at least 200 basis points following particularly steep drops in the Treasury yield. In fact, a recent analysis shows that since 1995, there have been 189 weeks (14 percent of total) when the spread was at least 200 basis points, driven by steep drops in the Treasury yield and/or rising global economic concerns. As evidenced by recent events, often the spread increases because mortgage refinance application processing capacity cannot meet demand, so lender-offered rates don’t follow the Treasury yield down one for one. So, while the mortgage rate has declined in response to the decline in yields, it is unlikely to fall by the same magnitude as the Treasury yield.

Will Negative Mortgage Rates Come to the U.S.?

The prospect of negative mortgage rates in the U.S. is another hot topic among economists. Nominal rates on sovereign debt have gone negative in Japan and Germany, and Denmark has shown that it is possible, even for mortgage rates, to be negative. If the yield on the 10-year Treasury is negative (highly unlikely), could it result in a negative mortgage rate? The short answer is probably not. In the U.S., mortgage rates would have to fall by more than 300 basis points to be negative. More importantly, mortgage rates tend to be higher than the Treasury yield because of costs of servicing, credit risk and prepayment risk. Even if the 10-year Treasury yield is negative, these costs remain positive, making a negative or even zero percent mortgage rate highly unlikely.

While it is highly unlikely that mortgage rates will turn negative, it is plausible that mortgage rates fall further if the benchmark 10-year Treasury bonds yield declines further. The Federal Reserve’s recent announcement that it would buy $700 billion in Treasury Securities and mortgage-backed securities can work to prevent mortgage-backed securities spreads from widening further to Treasury yields, increasing the likelihood of additional decreases in mortgage rates. It’s reasonable to expect that rates will fall even further and likely surpass the prior record low, but not necessarily one-for-one with the 10-year Treasury yield. However, mortgage rates must still account for the servicing, credit and prepayment costs that don’t disappear when the risk-free rate of return is low. So, how low can mortgage rates go? Today’s rates are already really close to the bottom.