Given the most recent release on housing starts showing a decline, many are asking if the housing market is stagnating. Builders fear that the decades of broad-based demand for single-family suburban homes is now a bygone era. Young millennials are pouring into the big city and eschewing homeownership permanently. Who, if anyone, will want to buy a home and what does that mean for the homeownership rate. Is the decline in housing starts the butterfly flapping its wings, the consequence of which will be dire for the housing market?

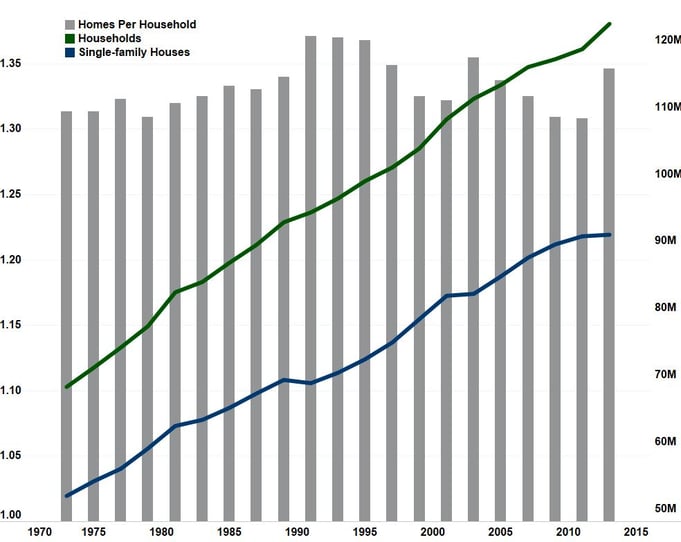

This summer, I spoke with Business Insider, pointing out that homeownership rates are not down due to a lack of housing availability. As shown in the figure, housing starts since the 1970s have consistently kept pace with the growth in the number of households. Over the long run, we typically increase the housing stock to keep up with demand created by new household formation. This is best shown in the number of homes per household over time, which has changed very little over the last 40 years. What’s important is the type of housing demanded – multi-family rental or single-family owner-occupied.

“For now, the amount of housing relative to the total number of households is just right. But, watch out. The type of housing demanded today is not going to be the type demanded tomorrow. Maybe ‘tomorrow’ is a little sooner than we all thought.”

It’s important to look beyond the headline in last week’s housing starts release. A closer look at the data reveals that the decline in starts was entirely due to multi-family housing starts declining by more than 40 percent over a year ago. In fact, single-family housing starts actually increased by more than 5 percent year-over-year. Keep in mind that single-family housing starts make up more than 75 percent of the total. So, is there a problem? I think not.

Since the end of the Great Recession, we have added more than 6 million rental households and actually lost more than a million owned households. Is it any wonder the overall homeownership rate is down? Builders have built to meet the rental demand. But now, as we should all expect, the shift to owner-occupied, single-family housing will begin to happen in earnest.

The lagging homeownership rate reflects the lifestyle preferences of the Millennial generation. Millennials are the most educated generation in American history and are therefore spending more time in school. They are delaying the decision to buy a home, as they get more education and wait to get married and have children.

After spending more time and money on their education, Millennials are more likely to place greater emphasis on building their career, paying off college debt, traveling and living in rental housing for the majority of their twenties. In contrast to previous generations, Millennials are putting off lifestyle decisions like marriage or buying a home or having a child until they are more established in their careers.

So, do we have the right number of homes given the overall demand for housing? Housing is a durable – actually very durable – good. The stock of homes built over the past 50 years provides a solid foundation (pun intended) to accommodate aggregate demand. In response to Baby Boomer demand, the number of homes gradually increased starting in the 1970s and reached a four-decade high in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, the number of homes per household experienced minor fluctuations, beginning with 52 million single family homes available for 68 million households in 1973, or one home for every 1.3 households. By 2013, there was one home for every 1.35 households, or 91 million homes for 122 million households. Is that too many, too little, or just right?

Millennials have spurred a large amount of multi-family housing starts in recent years, as they have demanded rental housing. Yet, in survey after survey, they have always stated the desire to ultimately become homeowners. For now, the amount of housing relative to the total number of households is just right. But, watch out. The type of housing demanded today is not going to be the type demanded tomorrow. Maybe “tomorrow” is a little sooner than we all thought.

Christina O'Connell contributed to this post.